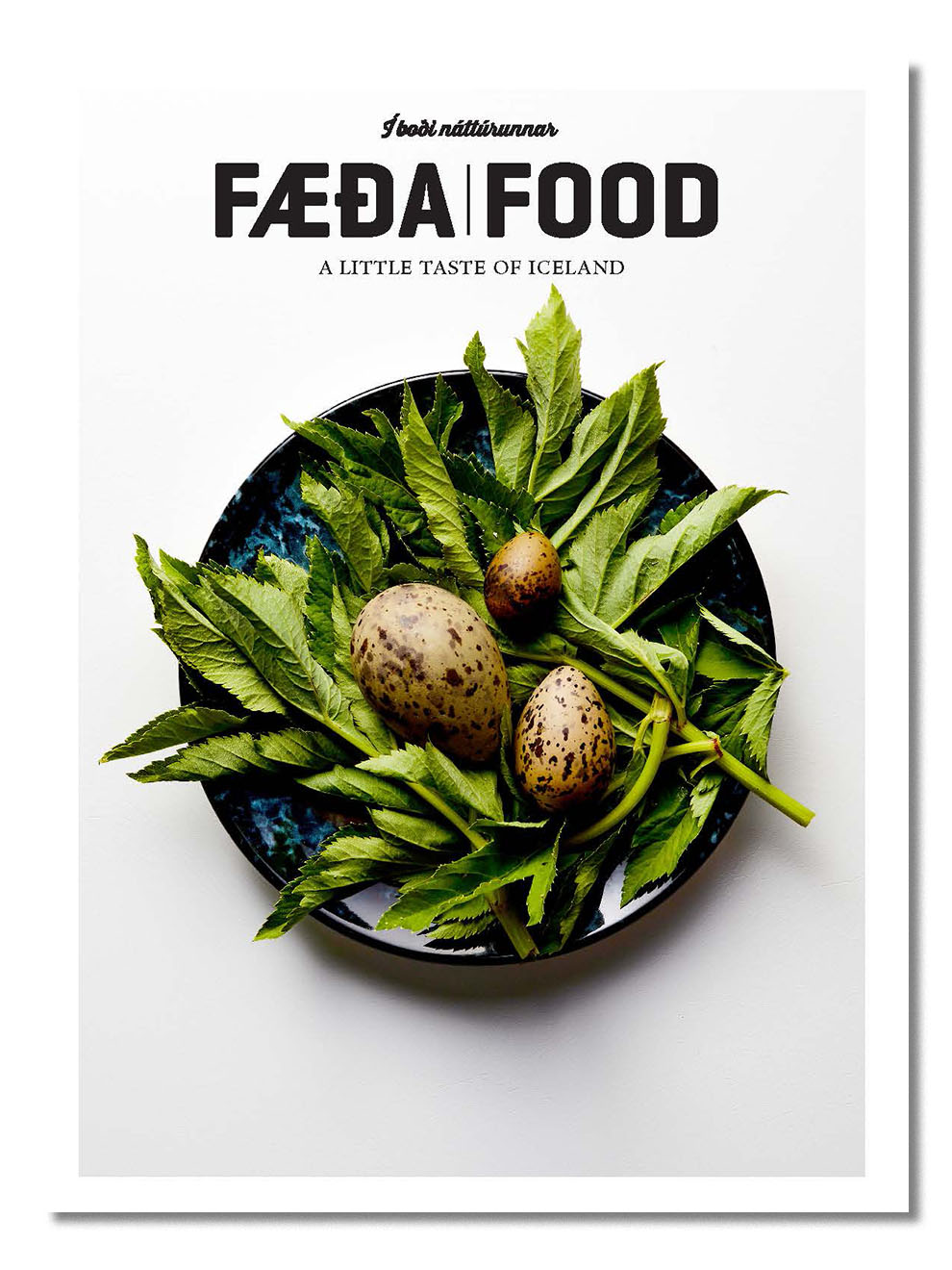

At the Chef’s Whim

Text GUÐBJÖRG GISSURARDÓTTIR

Photos GUÐBJÖRG, JÓN ÁRNASON and ÁSLAUG SNORRADÓTTIR

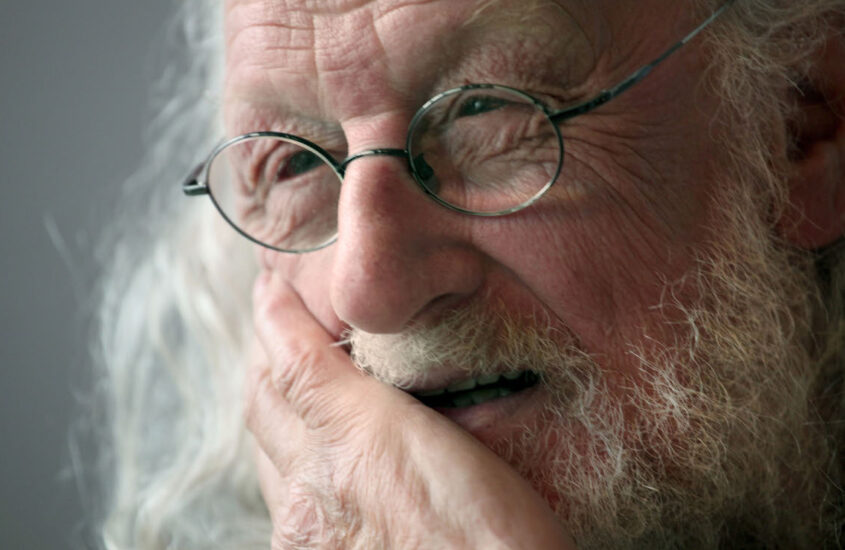

Decked out in a red clown nose and rose-patterned apron, Rúnar Marvins served an imaginative fish dish in a remote countryside hotel in the 80s, completely aware of the revolution in Icelandic cooking he would play a large part in. He is often considered the uncrowned king of Icelandic seafood cuisine, his hallmarks a mix of age-old traditions, making full use of food sources and innovative experimentation.

Rúnar was born and raised in Sandgerði on the Reykjanes Peninsula, the eldest of eight siblings. “I would have undoubtedly been put on ritalin today. They thought I was an insufferable kid and teen and sent me off to a farm when I was nine. But I always had a home with my grandmother and grandfather. My grandfather didn’t let anything slip by him. And when I’d been booted out everywhere else, I remember he put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Even the clumsiest of foals often grow up to be fine horses!’ That has always stuck with me,” Rúnar says cheerfully. He’s never been one to take the well-worn path in his career, but likes to say his guiding principles are chance, audacity and a healthy dose of recklessness.

“The cook never got a lot of glory on those boats. The thinking was that eating was a waste of time so meals weren’t meant to be enjoyed.”

“I entered the workforce early, going out to sea at 14—school was no good as I just wasn’t cut out to sit still. And as the youngest and lowest man on the totem pole, I was immediately made to cook for the guys. The cook never got a lot of glory on those boats. The thinking was that eating was a waste of time so meals weren’t meant to be enjoyed. When I started out, I didn’t know even know how to boil water but just had to make it work. The meals were nothing fancy at all: frankfurters, other sausages, forcemeat, roasts and a leg of lamb on special occasions. Once when I had just started cooking at sea, I remember Kallinn, which is what the captain was called, raised his mug and called out, ‘Bring out the coffee, you lousy cook, so I can wash this disgusting taste out of my mouth!’ And then and there I got my first rave review,” says Rúnar, who loves to tell a good story from his seafaring days. “At sea the meals often got funny names. Meat and meat soup were called Eyvindur and Halla, Eyvindur with snot was meat in curry sauce, leftovers were called gobble-it-up and a meat stew was a trainwreck,” Rúnar says laughing, as you always need a little humor with friends at sea. Later on, Rúnar would bring this tradition to Hotel Búðir where certain dishes were often given funny names as determined by each chef’s particular sense of humor. Snails Ready for Eviction, for example, often got a snicker from dinner guests when they were brought a plate of escargot.

Rúnar worked at sea for ten years, on boats, trawlers and other vessels, but in his freetime he dabbled with music and even joined a band for a while. At sea he was most often given the role of cook, which was sometimes a thankless job as cooks were held in low regard, relegated below deck literally beneath everyone else. But he quickly learned his way around the galley and was considered quite capable. Once back on land he worked at several restaurants, though mainly at Hornið with Jakob Magnússon, who became a good friend.

“When I started out, I didn’t even know how to boil water but just had to make it work.”

THE REVOLUTION AT HOTEL BÚÐIR

Rúnar’s true arrival in the Icelandic culinary scene was when he started cooking at Hotel Búðir, as diners went out of their way to visit this exceptional spot on Snæfellsnes peninsula. He offered not only an array of divine dishes but also a certain irresistible charm that bloomed around Rúnar and his cohorts. But how did he end up at Búðir? “One day my friend Jakob Fenger told me about some old hotel he’d seen way out in the countryside and asked whether we ought to go take a look. He was good with his hands and could envision the possibility. But it was an utter eyesore when we got there. Broken windows and animals has been rooting around the place. But there was something about it that spoke to us. So the two of us together with Jakob’s wife Gunnhildur Emilsdóttir and a baker called Patresía, decided to lease the building and open a hotel and restaurant. We had to put down a deposit of a million krónur, which, of course, none of us had. So that winter we took jobs at sea out of Ólafsvík for the fishing season to save up.

“No one thought to eat these fish. So we got permission to keep everything that was getting chucked. And when we got back to land we cleaned the fish and stored them in a unit we rented from a freezer plant.”

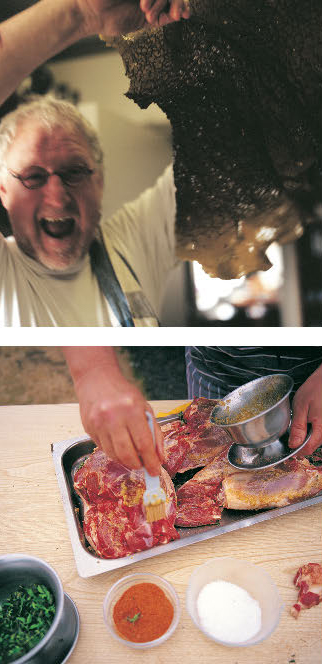

Back then everyone was fishing for cod, which was sold abroad, but we’d also bring in the odd unwanted haddock or two, a thorny skate and maybe two redfish. It always infuriated me when perfectly good fish was tossed back or sent to fishmeal plants just because they weren’t in fashion. No one thought to eat these fish. So we got permission to keep everything that was getting chucked. And when we got back to land we cleaned the fish and stored them in a unit we rented from a freezer plant. Word got around the fleet, which was about 30 ships. A lot of people liked our idea and gave us the throwaways from their catch. We did this all winter and in the spring when the season came to an end we had a 200-300 kg. mixed bag of what otherwise would have been tossed. And that summer the real fun began as we opened our doors with trumpets sounding. Tommi Jóns drew us this hippie poster that we had printed and hung up a few places—which was our entire marketing budget. And then came the wait. Often no one would come. And then one by one we’d get a guest. In the beginning people only came as hotel guests. But then word got out in the area that we had a license for beer and wine, the only restaurant on the peninsula at the time, and then the locals started to show up.

Our menu was really dictated by what came out of the crate of fish we’d collected over the winter. When we opened it we might find five different kinds of fish, and you can’t just prepare them all the same way. So recipes were born and evolved, and little by little I began to develop my own style. One notorious dish was flounder with bleu cheese, banana and garlic, which must’ve seemed like sheer insanity! Garlic was virtually unheard of at the time, but to my mind everything is better with garlic. We took redfish flambéed in cognac and served it with a dijon sauce and so on and so forth. Many times I had no clue what I was going to do with the fish until I made the evening’s menu. When I really got into a bind I found salvation in the phrase “at the chef’s whim”. The menu might include sautéed plaice “prepared at the chef’s whim” and then halibut followed by the same phrase and then maybe even a proviso at the bottom of the menu, ‘Please note: all dishes prepared at the chef’s whim!’. Which led people to ask, ‘And how is the chef feeling today?’”

Many times I had no clue what I was going to do with the fish until I made the evening’s menu. When I really got into a bind I found salvation in the phrase “at the chef’s whim”.

Over time, Rúnar has not done much to record the precise details of his recipes as much of his cooking revolves around improvising with the ingredients at hand. It wasn’t uncommon to see dishes marked “sold out” on the menu as there were only a few servings of each type of fish. “It wasn’t a problem in the beginning when there were just a couple of people showing up for dinner, but when we would get ten people on the weekends, the four of us thought that was a lot of work. In the middle of summer a journalist came from the Lesbók magazine of Morgunblaðið newspaper. He had monkfish in a port wine sauce and lost his mind. He described it as though the flavor had exploded in his mouth. When people are used to eating fish with only some melted mutton tallow, and maybe margarine and onion if you’re going all out, then you can understand the reaction. What’s more, monkfish was being thrown back at this time. After the write-up was published it was as though the flood gates had opened. We had to hire more staff and quick,” says Rúnar.

Next came restaurant critic Jónas Kristjánsson from Vísir newspaper, who had nothing but high praise for Rúnar’s food. In an article penned ten years after his fateful visit, Jónas describes the state of Icelandic cooking:

“Before the 1980-revolution, nearly all of Iceland’s trained chefs cooked alike: in the heavy-handed manner of the Danes during the interwar years. And after the revolution, nearly all of Iceland’s trained chefs have learned to cook alike: a relaxed version of French nouvelle cuisine. On of the reasons for this homogeneity is that everyone trains at the same academy—an excellent academy, but the same academy nonetheless.

In a way, Rúnar enjoys being the odd man out. He’s not a classically trained chef, but instead someone who has worked his way from the ground up, or rather from the waves up, as he started out as a fisherman. He is the Icelandic chef who most authentically operates in his own world.

I’m not dismissing the wisdoms of culinary school, although I do believe that Rúnar’s down-to-earth, self-taught style has been vital for our restaurant culture in recent years, especially what an uncommon perspective he brings. We get a different kind of food with Rúnar than with the others.”

Jónas gave Rúnar four and a half chef hats out of a possible five after his first visit. “We were suddenly a sensation all over the country,” Rúnar says with a smirk. “Our staff went from four to twenty and at our height we sent out 296 plates in one evening at Búðir. The last dish went into the dining room at 12:30 at night, and only then because we were out of everything,” Rúnar says, emphasizing the everything!

“I might have brought some orders out—as I often did when we got busy—wearing the rose-patterned apron my mom made me, a lopapeysa wool sweater and a red clown nose!”

One of Hotel Búðir’s draws was its relaxed and cozy environment, where artists were often among the guests and would sometimes sing or play instruments in return for dinner and a bed for the night. In fact, the chef himself was considered a spectacle in his own right. Rúnar amuses himself by recounting some of the dining room chatter. “Sometimes people would say, ‘The food was extremely good, but did you get a look at the chef?’ I might have brought some orders out—as I often did when we got busy—wearing the rose-patterned apron my mom made me, a lopapeysa wool sweater and a red clown nose! We made sure to not take ourselves too seriously. We never planned anything; it just happened.”

The wonderful adventure at Búðir lasted five years from 1980 to 1985, during which time Rúnar and seven partners acquired the hotel. But he grew tired of moving back and forth every spring and fall, as they weren’t equipped to stay open over the winter during this time. “I was ready to build a house and settle down at Búðir and keep it open all year. Maybe even set up a little kitchen to make fish cakes and plokkfiskur casserole to sell in shops. My seven partners thought I was nuts, and then I just lost interest,” he says, though it’s clear that he still has a strong connection with the place. They made magic there that can’t be replicated. Shortly after Rúnar and Sigríður Auðunsdóttir opened the restaurant Við Tjörnina in downtown Reykjavík.

“I had a great staff, so all I needed was to come in and do a good job.”

THE ADVENTURE CONTINUES

In 1986 the couple opened the restaurant Við Tjörnina, which, much like Hotel Búðir, was more or less stumbled into. “Sigríður had worked as an au pair for an American couple and stayed in touch with them. One year on a visit to the US I made them a pan-seared salmon in a dijon sauce, and they freaked out! They knew we ran Búðir in the summer and asked why we hadn’t opened a restaurant in Reykjavík. When I said we couldn’t afford it, they told us they could finance it and to start looking for a location when we got back. They would fund us whenever we were ready. And that’s how Við Tjörnina was born!” explains Rúnar. The couple had great support opening the restaurant in a distinctive, old building with a lot of homey charm. Sigríður decorated the place with hand-carved furniture, embroidered tablecloths and all the right bric-a-brac to conjure up a particular Icelandic nostalgia, not unlike the mood at Hotel Búðir.

“I had a great staff, so all I needed was to come in and do a good job,” says Rúnar, who carried on with his popular fish dishes. He added new items that often included unusual types of fish, which he managed to pick up here and there. But Við Tjörnina was one of the first restaurants in Reykjavík to offer only fish on their menu.

“I’ve never been a culinary student—I’m not performing under any expectations—so I don’t hold back”

When asked what about his cooking made it so popular, Rúnar says that he had just been playing around. “When I was young, food wasn’t something you enjoyed but rather fuel to keep you working, because we Icelanders don’t have a tradition of gourmet cuisine. But at that time attitudes towards food were changing. One of things I did at Búðir was to make my own broth, which was the all-important base for all my sauces. But fish wasn’t typically served with sauce. Icelandic chefs were much better at cooking meat, as people didn’t want fish when they went out to eat. Another thing I stressed was timing during cooking, not overcooking the fish, getting it out of the pan before it’s cooked through. And of course I was using different ingredients than the rest, not just unlikely types of fish but also herbs that I sometimes picked right from the heath. At Búðir I got to know Arctic thyme and sorrel, which is a prized ingredient, but no one here was using it. We also got some sidelong glances at the straw and wildflowers on our food, but people liked it. I’ve never been a culinary student—I’m not performing under any expectations—so I don’t hold back. This success is more attributed to luck than me trying to do something different,” Rúnar explains.

For 18 glorious years he was the chef at Við Tjörnina, which was, among other accolades, named one of the top five restaurants in Scandinavia during its time as well as receiving five out of five chef hats from restaurant critic Jónas Kristjánsson, who had remained a fan of Rúnar’s cooking all along.

“I’m retired now, but the people who have a taste for my food still sometimes ask me to cook for parties and other events.”

THE LEGACY

Today, 40 years after Rúnar launched his professional career at Hotel Búðir, he has returned to the Snæfellsnes peninsula, to Hellisandur to be exact, far from the hubbub of the restaurant industry. “I’m retired now, but the people who have a taste for my food still sometimes ask me to cook for parties and other events. And I always enjoy my two sons, who are chefs, and my daughter and grandchild. We work together during parties, and I think my grandchild likes cooking with grandpa,” Rúnar says proudly. Still, he’s hardly twiddling his thumbs; before the interview he had just come from the farmers’ market in Mosfellsbær where he was serving soup on the 10th anniversary of the cookbook he released with Áslaug Snorradóttir, Náttrúran sér um sína (Nature Takes Care of Her Own). Rúnar made a splash at the market, as he is wont to do—although now he’s got a stripy apron over this lopapeysa wool sweater and an even curlier mop. Rúnar answers the door just as he is, the quintessential country mouse, free of pretense but flush with good humor, a man immune to the passing trends—both sartorial and culinary. He’s a classic and it’s safe to say his has been a glorious and satisfying career. But I’ll give Rúnar the last word on that. “‘I haven’t lost anyone overboard yet!’, as [the cartoon cook-at-sea] Lási says. Mostly you’re just surprised and of course grateful that everything always works out in the end!”