Cheese of the North

Text DOMINIQUE PLÉDEL JÓNSSON

It’s not so long ago that skyr was only available at local dairy shops, where it was weighed and packed in parchment. Or it was simply made at home, especially in the countryside. When dairy shops disappeared in the 70s, skyr became available at the local grocery and then at supermarkets in plastic tubs. Fewer and fewer homes made their own skyr as it was easier to pick it up at the store. Today you can find “Icelandic skyr” in most supermarkets around the world, but what kind of skyr are we talking about?

Did you know that skyr is actually cheese?

Once collected, milk spoils quickly, and the most efficient way to store it is to turn it into cheese. In earlier times cheese (made with natural skyr cultures) was not allowed to firm up entirely. Instead a certain amount of liquid was left, which was made into a thick, sour skyr—a type of fresh cheese. Why it was done this way is not clear. Further south on the continent, cows and their keepers spent the whole summer roaming mountain pastures and in dairy huts where cheese was made, but in Iceland the summers are much shorter, so perhaps there’s wasn’t time to let the cheese mature? Or because they just found skyr more filling than normal cheese? Or because skyr was easy to preserve? Or any combination of these reasons. But this type of cheese wasn’t entirely unheard of elsewhere in Europe, whether it went under the name quark, faisselle or fromage blanc.

The Icelandic settlers brought the tradition with them from Norway, and skyr has remained a key component in Icelandic gastronomy every since. What we don’t know, however, is what skyr was like during those early days—it’s not unlikely that every household had there own take on skyr.

The industrialization of skyr

It’s relatively easy to make skyr at home, which is no surprise since it has been made at home for centuries. Skyr is an acid-set cheese where skyr from a previous batch is used to curdle the next. The whey created from the process was used to preserve meat (this type of preservation created a class of Icelandic foods called súrmatur or “sour food”, which are rarely today eaten except at special festivals in the late winter season of Þorri), as salt was not widely available and the manure VS. WOOD!! used in the smoking process was in short supply.

Skyr-making died out in Norway and the other Nordic countries but continued in Iceland, mostly likely because of how isolated and poor the island was at the time. What made skyr unique was that it was made from skim milk and carried much of the milk’s protein. And it’s made from these heritage skyr cultures that been preserved through the ages by uninterrupted skyr-making. Milk from cows, goats and sheep was used depending on what was available on the farm, but at the turn of century agriculture underwent huge changes and cow’s milk became the dominant supply.

“And it’s made from these heritage skyr cultures that been preserved through the ages by uninterrupted skyr-making“

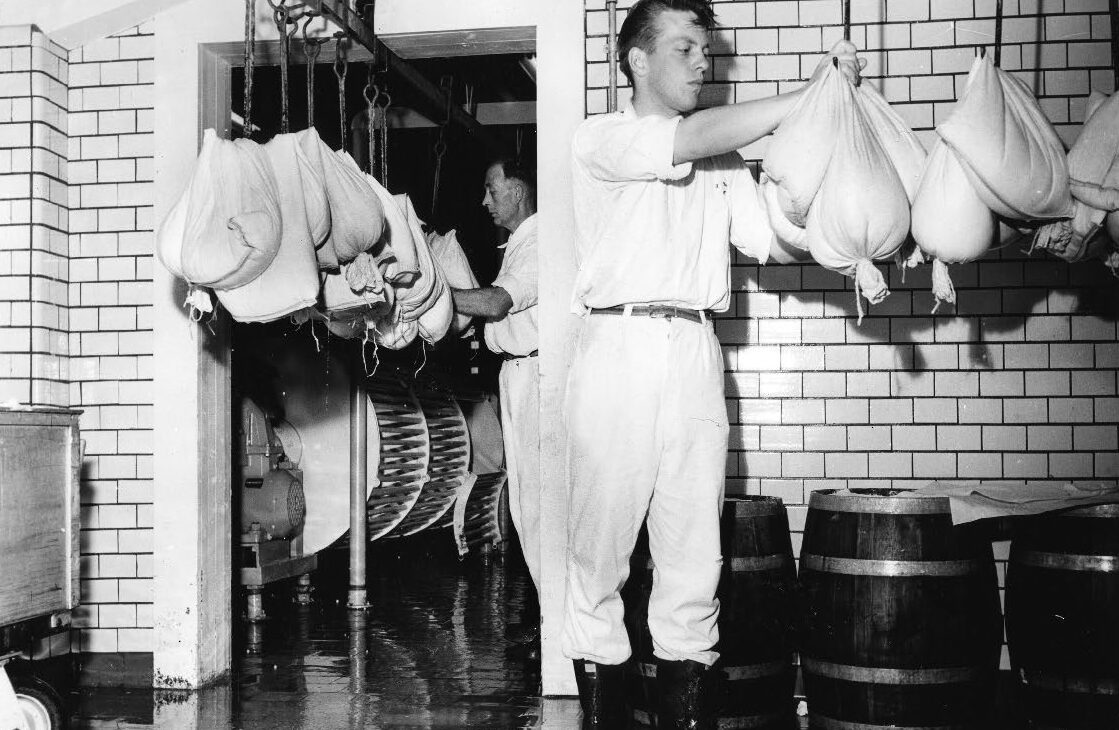

The nation has always consistently consumed skyr, but when the supply of manufactured skyr increased, so did consumption and growth has been steady every since. The production of skyr also changed during this industrialization, which arose because of, among other factors, high demand. Cloth straining, as was the practice for years, was far too slow for mass production and abandoned in favor of centrifugation and now even ultrafiltration. Bacteria can be difficult to control and sometimes unpredictable, which doesn’t lend itself to the industrial process, so the milk is now pasteurized and then cultures (freeze-dried yogurt cultures) and rennet are added. There’s no need now for starter skyr (a bit of skyr from the previous batch), as cultures are now made new with every batch and coagulation takes place inside the containers.

Skyr is not necessarily skyr!

Skyr was once made at all the country’s dairy farms, but their numbers have dwindled and dairy production has been consolidated into just a few companies. MS Iceland Dairies is by far the largest with all MS skyr produced in the southern town of Selfoss under several names including KEA, which was for years made in north Iceland. KEA’s pride was that their skyr cultures had been in continuous use since 1932, so plain skyr from KEA is probably still “good old skyr”. Other skyr products (like skyr.is and Ísey Skyr Bar) are made with yogurt cultures (sometimes called skyr cultures or lactic acid bacteria) and a process called ultrafiltration instead of straining the skyr in cloth bags. In recent years a few small manufacturers have carved out a niche for themselves using the traditional method. Arna in Bolungarvík has recently put on the market “strained skyr”, which is produced with traditional methods, plus the skyr is lactose-free. Erpsstaðir Creamery produces “country skyr”, which follows traditional production methods precisely. At Eftsidalur dairy farm skyr is packaged in parchment just as it was in the old days, whey is bottled and sold and real cream is used in their ice cream, as it is at Erpsstaðir. Bíóbú manufactures organic strained skyr but doesn’t use a starter from the previous batch to create the next. One of the newest additions is Skyrgerðin in Hveragerði, which is housed in one of the country’s oldest skyr factories. There you can buy authentic skyr and learn a little about its history at the same time. Home skyr-making is still practiced in a few areas in the country like Egilsstaðabúið farm, whose skyr is sold at Fjóshornið, a local shop in town.

Fame & fortune overseas

A little over ten years ago MS partnered with dairy producers in a few neighboring countries to manufacture skyr in exchange for royalty payments on sales. The reason was that the EU market was closed to Icelandic agricultural products excluded from the EFTA agreement. MS first partnered with the Danish dairy company Thiese Mejeri and Q-meireri in Norway. MS skyr is now available in the UK and exported to Finland and Switzerland. In the US, Siggi’s skyr (made with yogurt cultures) has become wildly popular at WholeFoods health food stores. MS has also launched a partnership in the US to produce Icelandic Provisions skyr. It’s difficult to find any reliable stats on the size of the market overseas, since direct imports account for so little, but it’s thought the market may be about €70 million (The Guardian). Iceland’s popularity among tourists seems to have boosted the sale of Icelandic skyr as well.

“Good old skyr”

In 2011 Matís, Iceland’s institute for food and biotech R&D, released a report entitled “The Distinct Qualities of Traditional Skyr” by Þóra Valsdóttir and Þórarinn E. Sveinsson, which states that traditional skyr does in fact possess certain distinct qualities, especially with regard to the food’s microbiome. This study was used by the local Slow Food chapter to apply for skyr’s inclusion in the so-called “presidia” of the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity. This declaration not only recognizes the unique qualities of traditional skyr on an international level, but also recognizes that traditional skyr has been subject to unfair competition. A detailed description of traditional skyr has been created as a collaboration among producers, Matís and specialists from Slow Food. This description is similar to those used to apply for protected status in Brussels to certify the authenticity of certain agricultural products and foodstuffs like PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication) for products like Prosciutto di Parma, Champagne and Gorgonzola cheese. Skyr was inducted into the Slow Food Presdia in the summer of 2015 and is the first Iceland product to be named as such. One way to safeguard this heritage is to protect the name “traditional Icelandic skyr”, which is the good old skyr we know. And that’s that!

In Iceland, traditional Icelandic skyr has been recognised as Slow Food Presidia. This recognition of the value of our cultural heritage also confirms that the Slow Food values concerning good food, unpolluted and fair for the producer as well as the consumer, are important to our future. Read more here.